Daniello Bartoli

Reverend Daniello Bartoli | |

|---|---|

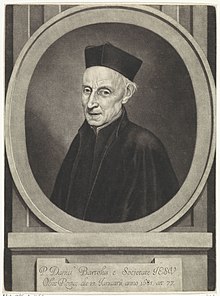

Portrait of Daniello Bartoli, 1685 | |

| Born | 12 February 1608 |

| Died | 13 January 1685 (aged 76) |

| Resting place | Ferrara Charterhouse |

| Other names | Ferrante Longobardi |

| Occupations |

|

| Parent(s) | Tiburzio Bartoli and Ginevra Bartoli (née Simeoni) |

| Writing career | |

| Language | Italian, Latin |

| Notable works | Istoria della Compagnia di Gesu L'huomo di lettere |

| Ecclesiastical career | |

| Religion | Christianity |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Ordained | 31 July 1643 |

Daniello Bartoli, SJ (Italian pronunciation: [daˈnjɛllo ˈbartoli]; 12 February 1608 – 13 January 1685) was an Italian Jesuit writer and historiographer, celebrated by the poet Giacomo Leopardi as the "Dante of Italian prose"[1]

Ferrara

[edit]He was born in Ferrara.[2] His father, Tiburzio was a chemist associated with the Este court of Alfonso II d'Este. When the papacy refused to recognize his illegitimate successor the court moved in 1598 under Cesare d'Este, Duke of Modena. During the Cinquecento and due to a host of writers including Ariosto and Tasso Renaissance Ferrara was the literary capital of Italian letters along with Florence, whereas the language of papal Rome was humanist Latin. His identity as a Ferrarese and a Lombard is touted in the pseudonym, Ferrante Longobardi which he used to sustain his independence from the linguistic tyranny of Florence in Il torto ed il diritto del "Non si può" (1655).

Vocation and Studies

[edit]

Daniello was the youngest of three sons and barely fifteen when embraced a vocation to the Society of Jesus in 1623.[3] Debarred by his superiors because of his manifest literary talents from the missions in the Indies he would later describe, he attained high distinction in science and letters. After a novitiate of two years at Novellara, Bartoli resumed his studies in Piacenza in 1625. In Parma (1626–29) he completed his philosophate and (1629–34) he taught grammar and rhetoric to the boys of the Jesuit collegio.[4] Under Jesuit scientists Giovanni Battista Riccioli and Niccolo Zucchi the young Bartoli, together with his younger contemporary Francesco Maria Grimaldi was involved in noteworthy experiments and discoveries of the planetary heavens. Bartoli along with Zucchi is credited as having been one of the first to see the equatorial belts on the planet Jupiter on May 17, 1630.[5] And in his old age he would return to the world of science. He was ordained a priest in 1634 and continued his studies in Milan and Bologna. In his thirties he was an esteemed preacher delivering the Lenten sermons at the principal Jesuits churches of Italy including Ferrara, Genoa, Florence and Rome. While in Ferrara he also published a collection of poems under the name of a nephew, as the Jesuits in Italy were not allowed to publish poetry. In his first published work he will quote from a number of these, anonymously. At 35 Bartoli pronounced his final vows as a professed Jesuit in Pistoia on July 31, 1643. In 1645 his treatise on the man of letters, L'huomo di lettere difeso ed emendato catapulted him to national celebrity and international fame as a leading contemporary writer of the High Baroque age. For the rest of the century his treatise was considered a masterpiece of erudition and eloquence. It became a staple of the Italian printing industry and was much sought after and translated. During the process of her conversion to Roman Catholicism at the hands of the Jesuits in the 1650s Christina, Queen of Sweden specifically requested a copy of this celebrated work be sent to her in Stockholm.[6] Heading to preach in Palermo he survived a shipwreck off Capri in 1646, but lost the manuscripts of his sermons.[7] Because of his growing fame his superiors put an end to his decade as an itinerant preacher and brought him permanently to the order's headquarters in Rome. In 1648 his was appointed Jesuit historiographer and spent the next four decades writing his great history, as well as moral, spiritual and scientific treatises.

Baroque Rome

[edit]

The remarkable success of Bartoli's literary debut coincided with the triumph of the High Baroque in Rome and it serves as a testament to the formative role of the Italian Jesuits as cultural entrepreneurs meditating between the sacred and the profane elements of the age. L'huomo di lettere (1645) became a cultural vademecum for the aspirations of a new generation of humanist intellectuals. Its eloquence and erudition found a lively balance between devotion to antiquity and consciousness of the modern. In Italy it was a bestseller. During the decades of Bartoli's life that followed, the work had editions and reprints nearly annually in Rome, Bologna, Florence, Milan and especially Venice. In the same period there were translations in French, German, English, Latin, Spanish and later Dutch. But history was his main task as a Jesuit man of letters. As such Bartoli represents the shift from the preceding Latin humanist historiography of Niccolò Orlandini and Francesco Sacchini to the illustrious Jesuit prose tradition he established in Italian when he undertook the official history of the first century of the Society of Jesus (1540). His monumental Istoria della Compagnia di Gesu (Rome, 1650–1673), in 6 folio vols. is the longest Italian classic. It begins with an authoritative, if somewhat ponderous, biography of the founder Ignatius Loyola.[8] Particularly fascinating and exotic are his histories of Francis Xavier and the Jesuit missions in the East which describe India and the opening of the East, L'Asia (1653) in eight books. A shorter work on Akbar the Great and Rodolfo Acquaviva came out in 1653 and was added to the third edition of L'Asia in 1667.[9] Part II of the first corner of the world he completed was Japan, Il Giappone (1660) in five books, and the Part III on China, La Cina appeared in four books (1663). To these he opened his projected Europa with the missions on the Jesuits in England, L'Inghilterra (1667) and a final work on the opening years of the order in the Italy of St. Ignatius, Diego Laynez and Francis Borgia, L'Italia (1673). With these histories he alternated treatises on language use, Del torto e del diritto del non si può[10] and moral works like La Ricreazione del savio.[11] In the 1660s the Lyons Jesuit Louis Janin, translator of L'huomo di lettere issued Latin translations of these histories. From 1671 to 1674 Bartoli served as Rector of the Collegio Romano in recognition of his international prestige as a writer. Indefatigible in his final years Bartoli produced 4 Jesuit biographies and three scientific treatises on pressure, sound, coagulation. His several works of spiritual reflection were brought together a folio edition, Le Morali in 1684. His final work, Pensieri sacri[12] went to press after his death in Rome, January 13, 1685.

During the early nineteenth century, of Leopardi and of Manzoni, Bartoli became the literary paragon as a master of prose style. Outstanding among the numerous printings and anthologies of his works from that period is the standard octavo edition of his complete works beautifully printed by Giacinto Marietti, Turin, 1825-1842 in 34 volumes.

Literary writings and historical works

[edit]

- Dell'huomo di lettere difeso ed emendato 1645

- La povertà contenta 1649

- Della vita e dell'istituto di s. Ignatio, fondatore della Compagnia di Gesù 1650

- Della vita del p. Vincenzo Caraffa, settimo generale della Compagnia di Gesù 1651

- L'Asia 1653

- Missione al gran Mogor del p. Rodolfo Acquaviva 1653

- L'Eternità Consigliera 1653

- Il torto ed il diritto del "Non si può" 1655 (under the pseudonym "Ferrante Longobardi")

- La ricreazione del savio 1659

- Il Giappone, parte seconda dell'Asia 1660

- La Cina, terza parte dell'Asia 1663

- La geografia trasportata al morale 1664

- L'Inghilterra, parte dell'Europa 1667

- L'huomo al punto, cioè l'huomo al punto di morte 1669

- Dell'ultimo e beato fine dell'uomo 1670

- Dell'ortografia italiana 1670

- L'Italia, prima parte dell'Europa 1673

- Della tensione e della pressione 1677

- Del suono, dei tremori armonici, dell'udito 1679

- Del ghiaccio e della coagulatione 1682

- In addition to his magnum opus, the Istoria della Compagnia di Gesu for which he wrote 6 volumes, as Jesuit historiographer Bartoli produced 5 Jesuit Lives: Vincenzo Caraffa 1651, Robert Bellarmine 1678, Stanislas Kostka 1678, Francis Borgia 1681, and his teacher, the astronomer Niccolò Zucchi 1682.

- Degli uomini e dei fatti della Compagnia di Gesu: Memorie storiche, an annalistic chronicle of the first Jesuit half century, (1540–1590), left in mss. at his death, was printed in five volumes by Marietti (Turin: 1847-56), in supplement to his 34 volume Opere.[13]

References and online links

[edit]Notes

- ^ Leopardi, Zibaldone (13 July 1823).

- ^ Birthplace marker

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Parma's Collegio dei Nobili trained the sons of the Catholic nobility

- ^ Denning, William Frederick (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 562–565, see page 562, para two, lines six and seven.

The belts were first recognized by Nicolas Zucchi and Daniel Bartoli on the 17th of May 1630

- ^ John J. Renaldo, Daniello Bartoli: A letterato of the Seicento (Naples,1979) p. 41 [1]

- ^ Della Vita del p. Vincenzo Carafa, Settimo Generale della Compagnia di Gesù (Rome, 1651) pp. 77-78. [2]

- ^ Della vita e dell'istituto di S. Ignatio, fondatore della Compagnia di Gesu (Rome, 1650)[3]

- ^ Missione al Gran Mogor del p. Ridolfo Acquaviva della Compagnia di Gesu, sua vita e morte (1653); Salerno (1998);(1714)[4]

- ^ (Rome: de Lazzeri, 1655)

- ^ (Rome: de Lazzeri, 1659)

- ^ (Venice: Storti, 1685)

- ^ Opere del padre Daniello Bartoli della Compagnia di Gesu, 39 volumes (1825-1856).[5]

Select Bibliography

- Avetta, Adolfo (1903). "Di alcuni giudizi letterari sul p. Daniello Bartoli". Rivista d'Italia. VI: 527–35.

- Gronchi, Giovanni (1912). La "Poetica" di Daniello Bartoli. Pisa: tipografia sociale.

- A. Belloni: Daniello Bartoli (1608-1685), Turín, 1931.

- D'Elia, Pasquale (1938). "Daniello Bartoli e Nicola Trigault". Rivista Storica Italiana. V. III: 77–92.

- Marzot, Giulio (1944). "Critica ed estetica del padre Bartoli e Seneca scrittore nel Seicento". L'Ingegno e Il Genio del Seicento. Florence: 101–131, 133–169.

- Pischedda, G. (1956). "La lingua e lo stile del Bartoli". Classicità provinciale. L'Aquila: 251–281.

- Gamba, Gigliola (1957). "Ricerche sulla lingua delle opere scientifiche di Daniello Bartoli". Archivio Glottologico Italiano. XLII: 1–23.

- Anceschi, Luciano (1958). "Gusto e genio del Bartoli". La Critica Stilistica e Il Barocco Letterario. Florence: 135–45.

- M. Scotti: Prose scelte di Daniello Bartoli e Paolo Segneri, Turín, 1967.

- Drake, Stillman (1970). "Bartoli, Daniello". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 483–484.

- Asor Rosa, A. (1975). Daniello Bartoli e i prosatori barocchi. Rome-Bari: Laterza.

- Renaldo, J.J. (1979). Daniello Bartoli: A Letterato of the Seicento. Naples: Istituto italiano per gli studi storici.

- Brutto Barone Adesi, M. (1980). "Daniello Bartoli storico". Rivista di Storia della Storiografia Moderna. 1: 77–102.

- Frei, Elisa (1984). "Through Daniello Bartoli's Eyes: Francis Xavier in Asia (1653)". Journal of Jesuit Studies. 9 (3): 398–414. doi:10.1163/22141332-09030005.

- Daniello Bartoli, storico e letterato. Atti del Convegno Nazionale di Studi Organizzato dall'Accademia delle Scienze di Ferrara (18 settembre 1985), Ferrara, 1986.

- Begali, Mattia (2007). "Daniello Bartoli". Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies. Vol. 1. New York: Taylor & Francis. pp. 133–136. ISBN 9781579583903.

- Ditchfield, Simon Richard (2019) The Limits of Erudition: Daniello Bartoli SJ (1608-85) and the mission of writing history. In: Hardy, Nicholas and Levitin, Dmitri, (eds.) Confessionalisation and Erudition in Early Modern Europe. Proceedings of the British Academy. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 218-239.

Modern editions

[edit]- Giappone. Istoria della Compagnia di Gesù. Milan: Spirali. 1985.

- B. Mortara Garavelli, ed. (1992). La Ricreazione del Savio. Milan: Guanda.

- B. Mortara Garavelli, ed. (1997). La Cina. Milan: Bompiani. ISBN 8845230082.

- Missione al Gran Mogòr. Rome: Salerno Editrice. 1998. ISBN 8884022444.

- Del torto e diritto del non si può. Milan: Fondazione Bembo/Ugo Guanda Editore. 2009. ISBN 9788860886132.

- Istoria della Compagnia di Gesù. L'Asia. Turin: Einaudi. 2019. ISBN 978-88-062-2837-8.

External links

[edit] Media related to Daniello Bartoli at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Daniello Bartoli at Wikimedia Commons- Asor-Rosa, Alberto (1964). "BARTOLI, Daniello". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 6: Baratteri–Bartolozzi (in Italian). Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. ISBN 978-8-81200032-6.

- Diffley, Paul. "Bartoli, Daniello". The Oxford Companion to Italian Literature. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- Daniello Bartoli at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- 1608 births

- 1685 deaths

- 17th-century Italian Jesuits

- 17th-century Italian historians

- Italian male non-fiction writers

- 17th-century Italian male writers

- Jesuit historiography

- Jesuit scientists

- Religious leaders from Ferrara

- Baroque writers

- Italian Baroque people

- Italian religious writers

- Italian Roman Catholic writers

- Italian science writers